Group rides are extremely popular among recreational and competitive cyclists. Although social interaction is a major incentive to ride in groups, so is safety. One technique cycling groups use to reduce the risk of collisions is riding double file, particularly in narrow lanes and when approaching intersections. This article discusses how riding double file can deter common crash types and what group cyclists should consider when choosing their position on the roadway.

Acting Visibly and Predictably

When cyclists operate in a disciplined, cooperative manner, they pose less danger to other bicyclists and are less likely to surprise motorists. Unfortunately, some groups ride in a disorganized and chaotic fashion, with bicyclists drifting or swerving about unpredictably, even crossing lane lines without looking for or yielding to other traffic. This creates uncertainty and stress for everyone. Preferred group cycling techniques involve maintaining one or more predictable lines, and moving out of a line only after looking for and yielding to traffic (of any type) that may be in the new line.

The default formation used by many experienced cycling groups is double file. Compared to single file, a double file formation makes the group more visible from behind and in front, and shortens the length of the group by half. This reduces the likelihood of the most common crash types faced by lawful, adult bicyclists: drive out, left cross, and motorist-overtaking.

Space Required for Passing

Most roads feature marked travel lanes that are too narrow for drivers of motor vehicles to pass a cyclist safely within the same lane. By attempting to pass within a typical 10′ wide lane on a rural road or city street, the driver of a pickup truck or SUV would strike a cyclist riding near the edge of the lane.

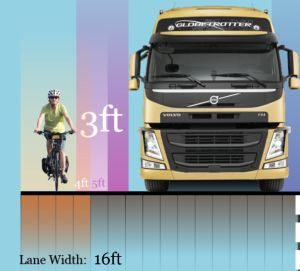

Bicyclists need a minimum of four feet of operating space to maintain balance and avoid surface hazards, and require at least three feet of passing distance for safety. In order to have proper clearance from wide landscaping trailers, commercial trucks, and transit buses, at least sixteen feet of pavement space is required. This space might take the form of a sixteen foot wide lane, a travel lane next to a wide paved shoulder, or a travel lane next to a bike lane (although road-edge cycling facilities sometimes pose their own problems).

Most roads in North Carolina don’t feature such pavement configurations. Most feature narrow lanes next to gutter pans or soft shoulders. Where paved shoulders exist, they are often poorly maintained or strewn with debris. On most roads, motor vehicle drivers must move into the next lane in order to pass cyclists safely. This means that the motor vehicle driver must look for and yield to other traffic before passing, and must be prepared to slow down and wait for an opening in the next lane.

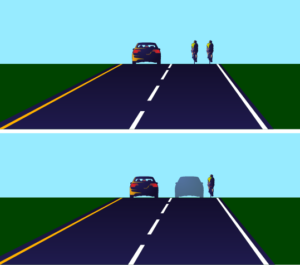

When cyclists ride near the right edge of a narrow lane, an overtaking motor vehicle driver may misjudge the remaining space in the cyclists’ lane, and fail to change lanes. This is the most common cause of car-overtaking-bicycle collisions in daylight. But when cyclists make it clear from a distance that a same-lane pass is not possible, motorists slow down earlier and plan their lane change sooner, reducing the cyclists’ risk of a sideswipe. One way cyclists can do this is by riding double file.

Experienced cyclists report fewer too-close passes and other near-collisions when riding double file than when riding single file near the edge of a narrow lane. Although double-file cycling is popular, actual rear-end collisions involving cyclists riding double file are extremely rare. The vast majority of overtaking-type crashes involves solo or single file cyclists at the roadway edge. Bicycling groups riding two abreast in daylight are highly conspicuous, making it easy for same-direction motorists to slow in time. The few media-reported crashes involving double-file cyclists generally result from hazards in front of the group, such as head-on collisions involving impaired drivers careening onto the wrong side of the road.

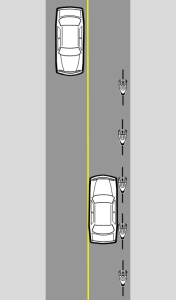

Contrary to what some cyclists may believe, most motorists don’t want to hurt cyclists. Riding double file helps motorists make the right decision when overtaking on a narrow-laned road. The figure at right depicts what a motorist sees when approaching cyclists from behind. Edge bicycling encourages motorists to imagine passing within the same lane when they aren’t close enough to judge the space accurately. Riding double file makes it clear from a long distance away that there isn’t room, so motorists can start planning safe maneuvers early.

The sight distance required to pass a small group of bicyclists safely on a narrow two lane road is usually much shorter than that required to pass a motor vehicle traveling near the maximum speed limit. As a result, many safe lane-change passing maneuvers on two lane roads are made by prudent motorists at locations that are marked with solid centerlines. An in-depth discussion of the evolving legal treatment of such passing can be found here. Regardless of centerline striping, a small percentage of motorists sometimes take risks by passing into the opposite lane when oncoming traffic is too close, forcing everyone else to compensate. While this is alarming and indicates a need for more effective driver education and enforcement, these incidents have not produced an epidemic of head-on collisions by any measure, and are a lower threat to public safety than the existing pattern of same-lane car-overtaking-bike collisions.

Junction Crashes

Most car-bike collisions occur at intersections, especially in urban and suburban areas. Because bicyclists are narrower than cars, they can be less noticeable to other drivers, especially if the bicyclist is traveling outside of a driver’s normal line of sight. A bicyclist can also be screened by other traffic and clutter in the road environment. Riding double file makes a group of bicyclists wider – as big as a car – and therefore makes them more likely to be seen and noticed.

The Drive-Out

The most common car-bike collision affecting adult road cyclists is the drive-out, where a motorist at a side street or driveway pulls into the roadway in front of the cyclist. In some cases drivers may misjudge cyclists’ arrival time, and in others they may fail to register cyclists’ presence or relevance. “I didn’t see him” is a common claim made by motorists in these crashes. In many cases, the claim is accurate.

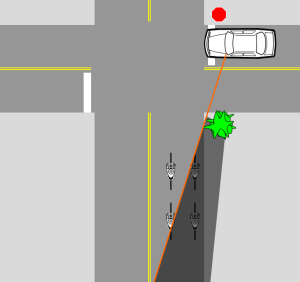

Drivers who are looking for traffic generally focus their attention near the center of the lane. Cyclists riding near the edge of the road are outside drivers’ area of focus, and can be concealed or camouflaged by poor sight lines and roadside clutter. The illustration at right shows how cyclists are less likely to be screened when riding farther from the roadway edge. Riding double file places the cyclists on the left hand side in a better position to be seen by drivers, and by making the group wider the cyclists will appear closer once they are detected.

The Left Cross

The second most common crash type affecting adult road cyclists is the left cross, where an oncoming driver turns left across the bicyclist’s path. This is also the most common collision type for motorcyclists, who, like cyclists, are also narrow. The sage advice given in motorcycle and bicycling safety courses is to “ride big” in as visible a location as possible, such as in the left hand tire track of other vehicles headed to the same destination.

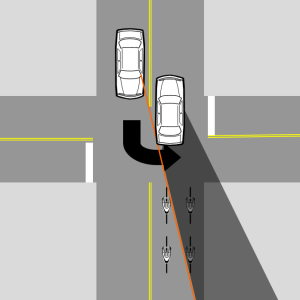

The illustration at right shows how cyclists at the right edge of the road can be screened from view from oncoming drivers preparing to turn left. Riding double file places cyclists in a position where the oncoming motorist is looking and is able to see them before starting the turn. The width of the group also makes them more conspicuous.

The Right Hook

Another collision type, common in urban areas, is the right hook, where a motorist turns right from a position to the left of the bicyclist. This can happen when a motorist attempts to pass a bicyclist immediately before turning, or when a bicyclist attempts to pass on the right side of a motorist who is about to turn right. Cyclists can can avoid this crash type by getting into line with other through traffic and staying away from the roadway edge where right turns are permitted. Riding double file encourages proper lane positioning by bicyclists at junctions and encourages right-turning drivers to wait behind the group instead of making a last-moment pass.

Intersection Thoughput

Cyclists must obey traffic signals and stop signs just like any other driver. These traffic controls divide intersection time among different directions of travel and effectively limit the traffic throughput at the intersection. Riding double file reduces by half the time required for the group to get through an intersection, reducing light signal cycles and delay for other road users as well.

Singling Up

When conditions are safe to encourage passing on two lane roads, such as where there is a wide shoulder in good condition away from intersections, most cycling groups will single up as a courtesy to other drivers. Group riders must make this decision cautiously. If the usable pavement narrows again before motorists have completed passing, cyclists may get sideswiped or a motorist may need to merge into the middle of the group. Communication, coordination and time are required for a group to transition between road positions and formations. As a result, cycling groups cannot exploit short-distance opportunities to facilitate motorist passing as easily as solo bicyclists can.

Platooning

Very large, contiguous groups of cyclists can make it particularly challenging for motorists to find a safe opportunity to pass in the next lane. Breaking large groups into multiple, spatially separated platoons of a dozen or so cyclists each can reduce the amount of time motorists must spend in the oncoming lane during each pass, easing gap selection. Platoons sometimes self-organize according to cyclists’ varying abilities. At the beginning of an organized ride, however, groups will usually move as one large mass. If organizers of group rides see a compelling reason to assist with motorists’ passing near the start of a ride, they may elect to begin the ride with separate platoons staggered in time. Some ride participants may resist this idea, however, preferring instead to ride en masse or to chase after other groups in front of them. It is difficult for ride organizers or other cyclists to control the actions of cyclists who are operating independently on public roads.

Rotation

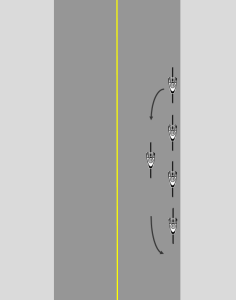

When riding in a paceline, the lead cyclist works the hardest against wind resistance, which accounts for 80% of a cyclist’s energy expenditure at speed. When the lead cyclist gets tired, she must rotate out and let another cyclist take over for a turn. This process, known as rotation, requires the lead cyclist to scan back for traffic that may be overtaking beside the group, and once the space is verified clear, move laterally and slow down until reaching the back of the group. This means that an additional line of bicycle traffic is created during the rotation.

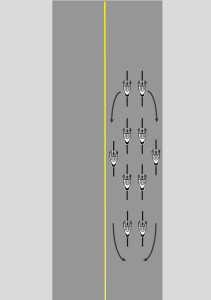

Common rotation patterns are designed to avoid disrupting the line of travel for the rest of the group, which improves safety. For example, consider a single-file paceline positioned at the right edge of a wide road to convenience motorists’ passing. If the leader were to drop back on the right, every other cyclist would need to move leftward across the lane to pass her. By rotating left (counter-clockwise), the lead cyclist is the only one who needs to look back and decide whether any other vehicles are so close as to pose a danger. Motorists who come upon the group after the rotation maneuver begins will need to wait or change lanes to pass them, but completing the rotation via this pattern will not produce any unpredictable or hazardous movements. Once the rotation is over, same-lane passing may continue if the group has chosen to facilitate it.

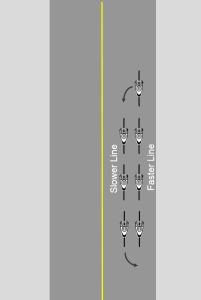

In a double paceline, rotation may happen on one or both sides of the group. If the two leaders coordinate to rotate out at the same time, they may both rotate to the left, adding one new line of bicycle traffic. But if the right-hand leader wants to rotate out alone, the left-hand leader blocks the direct path to a left-side rotation, and the right-hand leader may not have enough strength to accelerate ahead and around. Instead, the right hand line will usually rotate to the right.

A group of cyclists planning on rotating to both sides of a double placeline will position itself in the center of the lane to provide room for rotation on both sides. Depending on which side(s) the rotating cyclists use, rotation can give the appearance of bicycling three or four-abreast in a single lane for short periods of time. However, the alternatives are less desirable. For instance, singling-up during each rotation to limit the group to no more than two lines of bicycles would double the length of the group, making overtaking in the next lane more difficult.

It is important for the group to cooperate to ensure that cyclists do not collide or crowd one another, and that rotating cyclists do not get forced into the next lane or off the roadway if the lane is narrow. Two-sided double-paceline rotation is most common among experienced road cyclists who ride together as a group regularly, such as competitive cyclists on training rides. Falls and collisions with other cyclists are the most common causes of injuries to cyclists. For safety, cycling in close proximity requires skill, order and discipline. Frequent changes to the group configuration create increased opportunities for collisions between cyclists.

A more advanced form of double paceline is the continuously rotating paceline. It operates much like the rotation of a single-file paceline, except that the ride leaders rotate out almost immediately, and half of the cyclists are using the slower, left line at any one time. This pattern requires much more skill and coordination than the other paceline techniques, and so is not commonly used, particularly in beginner or mixed-skill groups.

Summary

Cyclists may operate two or more abreast for a variety of compelling reasons, including safety and efficiency. Using a full lane does not create a hazard for cycling groups and in some cases reduces risk. Transitions between different formations (particularly between lane-controlling and lane-sharing formations) pose the most significant risks to cyclists in a group.

See Also

Riding Two Abreast by Peter Wilborn of Bike Law

Overtaking a Group of Cyclists by Cycling Safety Wexford

Legal Issues about Riding Single File by BikeWalk NC

Safe Passing and Solid Centerlines by BikeWalk NC