Advocates for motoring sometimes call for elimination of bicyclists or pedestrians from roadways, or for increased regulatory burdens to be placed on bicyclists (ostensibly to equal the expense of motoring regulations). Their argument often begins with the motoring-centric assumption that roads are for cars, and that because motoring on roadways is regulated as a privilege, then any use of roadways is also a privilege, and not a true right. Historically and legally speaking, however, this claim is inaccurate. Recognition of an individual’s basic right to travel on shared roads dates back thousands of years.

Roads evolved from unimproved footpaths and trails over five thousand years ago. Some roads were constructed and maintained by private landowners, and others by governments. The earliest challenges to public travel over these routes came from landowners or other local inhabitants who might extort money from travelers or block travel by force or physical obstruction. Public use of roads was compelling for access to water, food, and trade, for transport of goods and materials, and for military purposes. Across the world, laws evolved to define the rights and responsibilities of travelers and landowners.

Some of the first written descriptions of travel rights are found in second century BC Roman property laws that established a hierarchy of easements that prioritized pedestrian access over wagon passage. The Romans were prolific road builders, creating a network of durable paved highways that spanned most of Europe including England. While of strategic military importance to the Roman government, these roads were public ways permitted to all. Any act to block or hinder travel upon public roads was prohibited by Roman law. Within the city of Rome, traffic congestion became such a nuisance that Julius Caesar banned wheeled traffic in the city during most of the daytime.

The tradition of public passage, however, survived even in the dark ages. In the twelfth century, the seminal English law text Tractatus of Glanvil written for Henry II declared the legal status of the king’s highway and the public right to travel upon it.

The concept of right of way originated in English law at this time with a dual meaning: First, the right of the king to establish public roads across private properties, and second, the public’s right of passage on such ways. The common-law right to travel on public ways followed the colonists to North America.

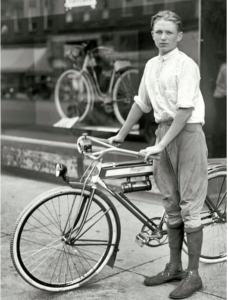

In the late 1800s controversy erupted over a new type of vehicle that was speeding along rural roads and urban streets, occasionally frightening horses and pedestrians: the bicycle. Considered a nuisance by some non-bicyclists, cities and states enacted numerous bans on bicycle travel (for instance, Kentucky banned bicycles from most major roads). Numerous court cases involving bicyclists’ road rights resulted in inconsistent outcomes. In cases involving collisions, English and American courts eventually concluded that the rules of the road for carriages should apply equally to bicyclists. These rules prohibited speeding or otherwise operating in a manner dangerous to others.

Eventually the higher courts in the states would reach conclusions protecting the right to travel by bicycle on public roads. In Swift vs City of Topeka (1890) the Kansas Supreme Court stated:

“Each citizen has the absolute right to choose for himself the mode of conveyance he desires, whether it be by wagon or carriage, by horse, motor or electric car, or by bicycle . . . . This right of the people to the use of the public streets of a city is so well established and so universally recognized in this country that it has become a part of the alphabet of fundamental rights of the citizen.”

In the case of the self-propelled automobile, however, the Kansas Supreme Court spoke too soon. In the 1890s, automobile travel was primarily a novelty for the wealthy, but motor traffic volumes and speeds grew quickly on public roads over the next thirty years. With popularization of motoring came a staggering epidemic of crash fatalities and injuries for pedestrians and vehicle operators. In response, cities across the country enacted new regulations on motoring ranging from licensing requirements to outright bans. Automobile organizations challenged the regulations in court based on right-to-travel grounds, and won many of the early cases. But as motoring’s death toll continued to increase each year, and government regulators made a stronger case that improper motoring violated the travel rights of others, the courts relented. By 1920, no court found the right to travel to be sufficient grounds to strike down a driver license requirement for motor vehicle use. For instance, in the federal case Hendrick v. Maryland 235 US 610 (1915):

“The movement of motor vehicles over the highways is attended by constant and serious dangers to the public, and is also abnormally destructive to the ways themselves . . . In the absence of national legislation covering the subject a State may rightfully prescribe uniform regulations necessary for public safety and order in respect to the operation upon its highways of all motor vehicles — those moving in interstate commerce as well as others. And to this end it may require the registration of such vehicles and the licensing of their drivers . . . This is but an exercise of the police power uniformly recognized as belonging to the States and essential to the preservation of the health, safety and comfort of their citizens.”

Drivers who were charged with driving a motor vehicle without a license would continue to attempt a defense based on the right to travel, but to no avail. For instance, in State v. Davis (Missouri 1988):

“The state of Missouri, by making the licensing requirements in question, is not prohibiting Davis from expressing or practicing his religious beliefs or from traveling throughout this land. If he wishes, he may walk, ride a bicycle or horse…. He cannot, however, operate a motor vehicle on the public highways without … a valid operator’s license.”

The State v. Davis decision calls out the importance of walking and bicycling in supporting the right to travel. If driving a motor vehicle is an issued and revocable privilege, then it stands to reason that some other modes must remain in order to preserve the right to travel. Otherwise, only the privileged could continue to travel independently on the essential trips that people have been making for thousands of years.

Bicycle registration programs are often proposed and sometimes implemented to combat bicycle theft and to raise revenue. Most government-operated bicycle registration programs in the US fail due to high implementation costs, low participation and revenue, complications for bicyclists traveling between jurisdictions, and increased friction between police and low-income populations. Today, Hawaii is the only US state with a mandatory bicycle registration requirement, which succeeds primarily because it is implemented as an excise tax on new bikes at the point of sale, and also because out-of-state bicyclists cannot ride across the state’s border.

As a note, property taxes have historically been the revenue method for paying for roadways. The high costs of the construction and maintenance of roads due to motoring, compared to traditional human and animal powered means, led to the institution of a fuel tax. Although the first gas tax was instituted around 1932, dedication to highways and the Highway Trust Fund wasn’t in place until 1956. According to a 2015 report done by the US PIRG, the fuel tax today covers less than half the costs of maintaining and expanding roadways. The resulting shortfall is made up from other sources of tax revenue at the state and local levels, and is generated by drivers and non-drivers alike. Most communities elect to promote the public benefits of bicycling and walking rather than deter these activities by applying a usage tax.

Many US residents do not drive motor vehicles due to limitations of age, health, or economics, or simply by choice. Worldwide, motorists are a clear minority; people outnumber motor vehicles 7 to 1. In much of the world, the bicycle is the most popular vehicle choice for travel, essential for the mobility of people with modest incomes or in areas with a scarcity of space that can be dedicated for motoring (or even for parking). Promotion of motoring at the expense of bicycling and walking would repurpose our roads from public rights of way open to all users into specialized facilities reserved for the privileged.

The only roads legally prohibited to bicyclists and pedestrians in North Carolina are fully controlled access highways, aka freeways. Prohibition from such highways is acceptable only because the full control of access prohibits driveway access between the highways and the adjacent land; the adjacent properties are accessible by other roads that are not fully controlled access and therefore open to bicyclists. The prohibition from fully controlled access highways does not prevent pedestrians and bicyclists from reaching their destinations, but may sometimes require longer routes.

According to the Complete Streets policy adopted by the North Carolina Board of Transportation in July 2009, “[t]he North Carolina Department of Transportation, in its role as steward over the transportation infrastructure, is committed to providing an efficient multi-modal transportation network in North Carolina such that the access, mobility, and safety needs of motorists, transit users, bicyclists, and pedestrians of all ages and abilities are safely accommodated.” The NCDOT Roadway Design Manual says “It is the responsibility of the Section Engineers and Project Engineers to be assured that all plans, specifications, and estimates (PS&E’s) for federal-aid projects conform to the design criteria in the “A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets” (2011).” That document, also known as the AASHTO Green Book, states: “The bicycle should also be considered a design vehicle where bicycle use is allowed.” It should be clear that bicyclists are intended users of all roadways in North Carolina except fully controlled access highways (freeways), and that it is our government’s job to facilitate this travel, not deter it.