Bicycling in the left half of a travel lane provides substantial safety advantages in common traffic scenarios. Knowledgeable bicyclists who ride between the lane center and left tire track improve their maneuvering space, sight lines, and conspicuity to other drivers. This reduces the risk of typical car-bike crash types such as drive out, left cross, right hook, motorist overtaking and dooring collisions. North Carolina’s existing vehicle code assigns bicyclists the same full legal right to a marked travel lane as any other driver, allowing bicyclists discretion to choose their position within their lane based on context. (NC does not currently have any bicycle-specific law restricting where in a marked lane bicyclists may operate as an inferior user class; see this history article for details.) Bicyclists in NC may operate at the right side of their lane when they want to encourage passing, and farther left when they wish to increase their visibility and maneuvering space and to deter same-lane passing.

All of the major adult bicycling education programs in the US, Canada, and Britain (e.g. LAB TS101, CyclingSavvy, IPMBA certification, CAN-BIKE, and British Cycling Bikeability) teach these variable lane position techniques. Some bicyclists reserve a leftward lane position for special situations, while others find it to be the preferred default, or primary position, moving right when they feel it is safe to do so (differing preferences likely reflect different local road conditions and experience). The utility of bicyclist lane positioning in the center and left half of a marked travel lane is recognized in mainstream traffic engineering publications such as the 2013 ITE Traffic Control Devices Handbook. It is increasingly common for traffic engineers across the USA to endorse and encourage bicyclist positioning in the center and slightly left of center of marked travel lanes in various situations through the installation of shared lane markings (aka “sharrows”) and Bicycles May Use Full Lane signs. However, the benefits of operating in a leftward lane position are not well understood by the general public. This article presents the basic operational principles responsible for the effectiveness of leftward lane positioning as a collision deterrent, and examines the implications of NCDOT’s proposal to change our state’s traffic laws to explicitly prohibit bicyclists from exercising these defensive driving methods.

Deterrence of Drive-Out and Left-Cross Collisions

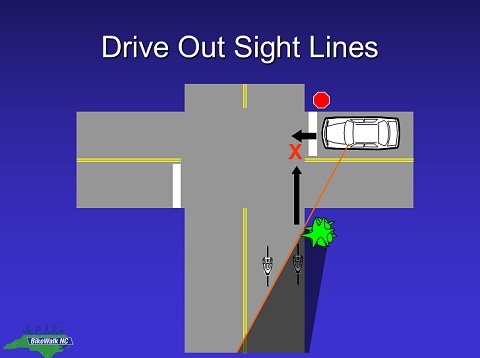

The two most common types of car-bike collisions that happen to lawfully operating bicyclists are the drive out and the left cross. These are also common collision types for lawful motorcyclists (who learn similar defensive lane positioning techniques through motorcycle safety programs). In the drive-out crash, a motorist at a side street or driveway fails to yield to the bicyclist on the priority route before pulling into the roadway, as shown in the figure below.

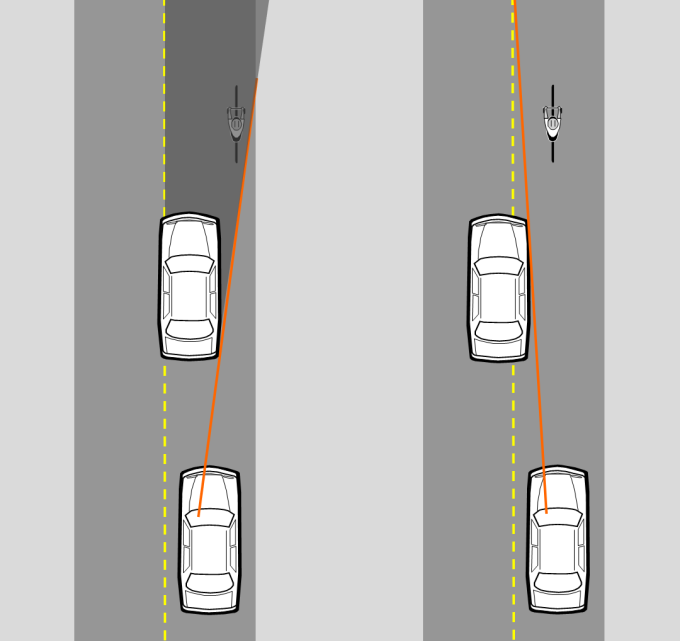

Drivers typically scan for approaching traffic by focusing on the center of the approaching lanes, and often fail to notice approaching traffic at the edge of the road. Note that a bicyclist at the right side of the roadway is more likely to be screened by roadside sight line obstructions than is a bicyclist riding closer to the center of the roadway. A bicyclist operating in a leftward position is not only more likely to be noticed, but also has more space and time for emergency maneuvering should the motorist enter the roadway.

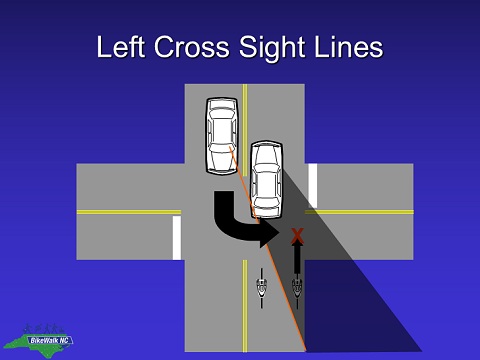

In a left cross collision, a left-turning driver fails to yield to an oncoming bicyclist. The driver may fail to see the bicyclist, fail to register the bicyclist as relevant, or misjudge the arrival time of the bicyclist. In some cases, the left-turning driver’s view of the bicyclist is screened by other traffic until moments before the collision, as shown in the figure below.

Because the left-turning driver’s best view is at the left portion of the oncoming lane, a bicyclist who operates farther left in the roadway is more likely to be noticed in time than a bicyclist who rides at the right side. A bicyclist in a leftward position also has more time to observe the left-turning driver and begin braking if necessary. When approaching intersections where other traffic may drive out or turn left, the preferred defensive bicycle driving position is in the left half of the bicyclist’s travel lane.

Deterrence of Right-Hook Collisions

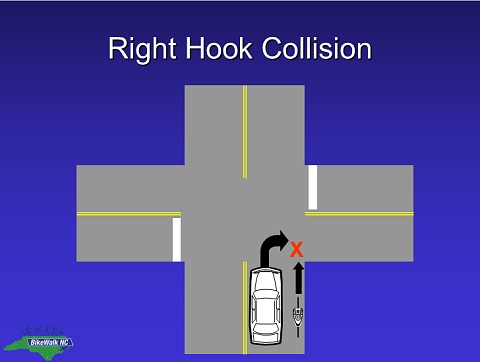

A right hook collision involves a right turning motorist positioned to the left of a bicyclist traveling straight, as shown below.

In some of these collisions the bicyclist overtakes on the right side of the motorist prior to the motorist’s turn; in others the motorist overtakes the bicyclist just before turning. In both cases, the underlying failure is improper lateral positioning relative to the different destinations. A right turning driver is legally required to approach and execute the right turn from a position as far to the right as practicable, and the bicyclist, like any other driver, is prohibited by state law from passing on the right unless in a separate marked travel lane. An effective way for a bicyclist to proactively deter right-hook collisions is for the bicyclist to merge into the center or left half of the travel lane when approaching a location where right turns are permitted and/or likely. This encourages right-turning drivers to wait behind the bicyclist rather than passing immediately before turning, and integrates the thru bicyclist into the normal traffic queue at an intersection rather than enabling the bicyclist to pass stopped traffic on the right.

Deterrence of Overtaking Collisions

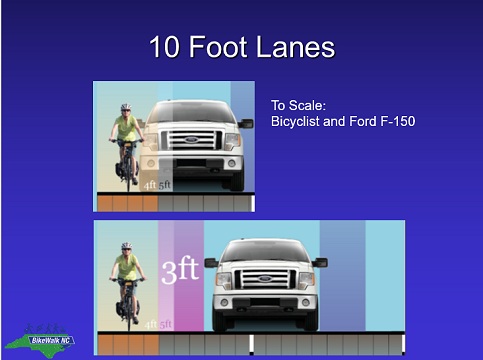

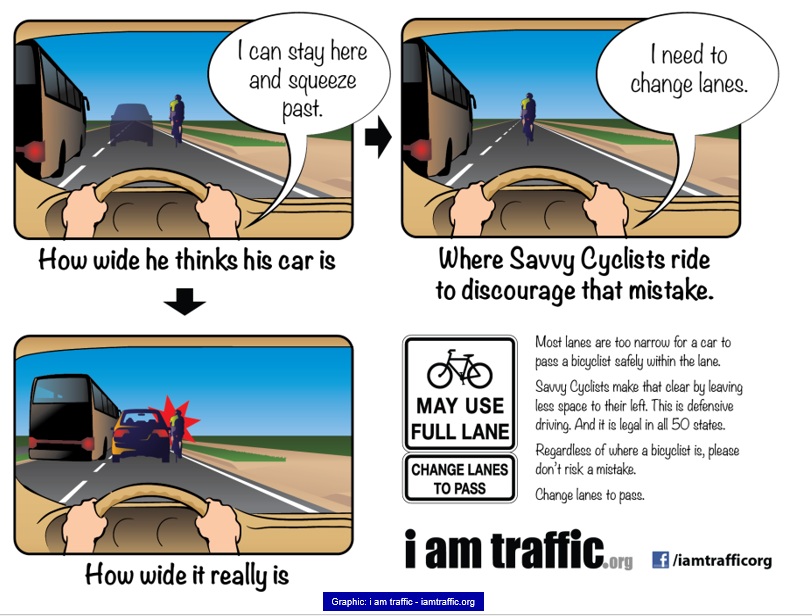

Motorist-overtaking-bicyclist collisions have a variety of causes, including drunk driving, distracted driving, drowsy driving, and bicycling at night without adequate visibility equipment. The most common cause, however, is a motorist attempting to pass within the same too-narrow lane as the bicyclist. Because most travel lanes are between ten and twelve feet wide, most same-lane passes are unsafe passes. The figure below shows that in order to safely pass a bicyclist riding on the right side of a ten foot lane on a typical rural NC road, a Ford F150 driver must drive most of their vehicle into the adjacent lane; a same-lane pass is practically guaranteed to sideswipe the bicyclist.

In a typical sideswipe scenario, the motor vehicle driver sees the bicyclist ahead, but attempts to pass without planning a safe movement into the adjacent lane. In many cases there is traffic in the next lane, which may require waiting before making a lane change, or there may be a barrier such as a raised center median. The underlying error is a failure to recognize the space required to pass safely until it is too late for the driver to avoid a sideswipe collision, as depicted in the figure below.

Most motorist-overtaking-bicyclist sideswipe collisions in North Carolina occur on state roads posted 40 mph or higher. Most such roads have travel lanes between ten and twelve feet wide. Motorist-overtaking-bicyclist collisions are very rare on low speed streets regardless of lane width. Higher speed means that a motorist must recognize the inadequacy of the lane width at a longer distance away, and also that collisions are more severe. One way that bicyclists can communicate the inadequacy of their lane width for same-lane passing is by cycling close to the center of the lane. This defensive positioning, called lane control, makes motorists more likely to recognize the unavailability of the bicyclist’s lane for passing at a long distance away, as depicted in the figure above. Lane control results in earlier, safer lane changes and fewer erratic maneuvers and sideswipes. Bicyclists find lane control to be most important for deterring unsafe passing in situations where the lane is narrow and adjacent traffic or barriers may tempt drivers into squeezing by within the bicyclist’s lane.

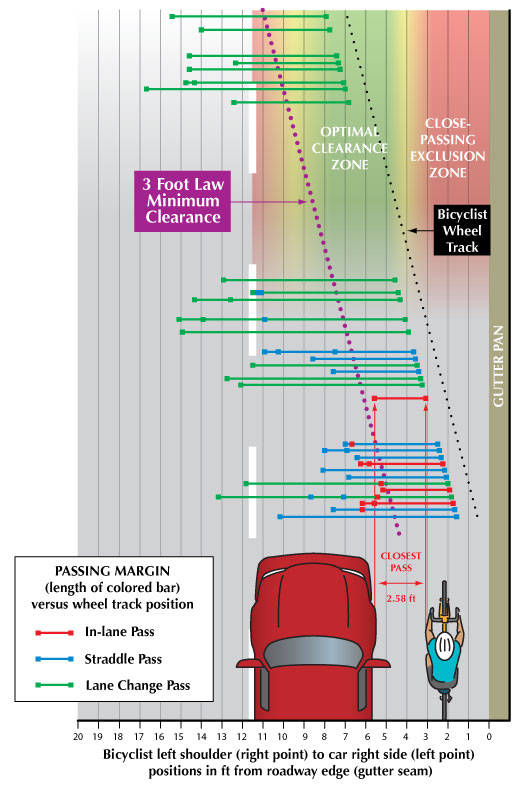

Exactly where is the ideal lane position for deterring unsafe close passing? Many experienced cyclists claim that a position between the center of the lane and the left tire track provides the best results. In a 2009 study, independent researchers Dan Gutierrez and Brian DeSousa performed instrumented experiments in an effort to quantify the effects of lane position on overtaking distance. Within the limits of their study, the fewest unsafe close passes occurred when the bicyclists were positioned between the center of the lane and the left tire track. The closest passes occurred while riding near the right tire track. A graphic summarizing their results is provided below.

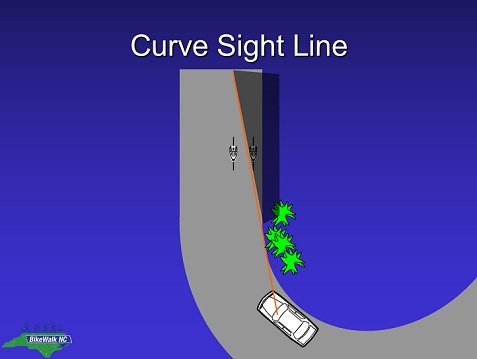

A leftward position in the lane also makes a cyclist more likely to be seen by an overtaking driver by putting the cyclist where the driver focuses their attention, reducing screening caused a vehicle passing in the same lane, and by improving sight lines at right curves, as shown below.

Deterrence of Dooring Collisions

Opening car doors are a leading cause of bicyclist injury in urban areas. A bicyclist may be startled by an opening door and swerve left into overtaking traffic, or may strike the opening door with the handlebar, and be thrown violently left into the travel lane, landing on their head or back. Cycling safety experts instruct cyclists to stay at least five feet from parked cars in order to avoid being struck or startled. A video demonstrating the derivation of this recommended distance can be seen here. This five foot minimum door zone distance puts bicyclists in the left half of the adjacent lane on some streets. On other streets, with wider lanes, the five foot minimum distance puts the bicyclist in a position where they face potential sideswipes from motorists attempting to squeeze by within the remainder of the lane. For this reason, bicycling safety experts recommend cycling in the center of the effective lane width that excludes the door zone if that effective lane width is narrow. This puts the bicyclist left of center of the full lane width on many urban streets. A discussion of door zones, effective lane width and recommended positioning of shared lane markings is provided in Chapter 14 of the 2013 ITE Traffic Control Devices Handbook. The Handbook’s Table 14-5 (copied below) of recommended positioning of shared lane markings in various lane widths adjacent to on street parking indicates positions that are well left of the center of the travel lane.

Avoidance of Surface Hazards

The right side of the road tends to attract debris such as broken glass, broken vehicle parts, sand, and gravel, and suffers the most pavement defects such as patched utility excavations. Drainage grates and vertical ridges along the gutter pan make the right edge especially treacherous. These hazards compel bicyclists to ride farther left in order to avoid falling or swerving. The usable, effective width of a travel lane is often perceived to be much narrower by bicyclists than by other road users.

NCDOT’s Proposed Prohibition on Bicycling in Left Half of a Marked Lane

In its final Report on the H 232 Bicycle Safety Laws Study, the North Carolina Department of Transportation contravened the unanimous vote of its own study committee, and recommended that the state legislature enact a new law that would prohibit bicycling in the left half of a marked travel lane. NCDOT provided no credible rationale or data to support its recommendation, leaving the bicycling community to speculate that perhaps NCDOT wants the left half of the lane left empty in order to support same-lane passing by motorists. BikeWalk NC opposes this proposed law because it would interfere with exercise of the defensive bicycle driving practices described in this article. Police who see bicyclists operating in the center of the lane (with the left half of their body in the left half of the lane) or close to the left tire track will view this positioning as unlawful, resulting in needless harassment and ticketing of the safest bicyclists on the road. Such a law would also have a chilling effect on bicycling safety education by potentially restricting teaching of effective defensive bicycling techniques.